Applying to Daycare (Hoikuen) in Japan

Last Updated on August 24, 2024 by Kay

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning I may earn a small commission on any purchases through those links at zero additional cost to you. Whatever I make goes to keeping this website running and I am forever grateful for the support. See my Privacy Policy for more information.

Wondering all there is to know about daycare in Japan?

Japan is known for having an overwhelmed daycare system, especially in large cities that have long waitlists due to a lack of daycares and daycare workers. I wasn’t expecting that my daughter would have a chance at getting into daycare as we live in a very popular area for families with very long waitlists, so you can imagine my surprise when she successfully got into a ninka hoikuen (authorized daycare) before she turned one!

My daughter attended two kinds of daycares in Japan and had a great time, so I thought it would be helpful to write a short series of articles about my experience with daycares in Japan, starting with an overview of the Japanese daycare system and how I applied.

Table of Contents

Types of Daycares in Japan

There are two major types of daycares in Japan, and it’s important to know the difference when it comes to deciding where you want to apply to and feel comfortable leaving your baby.

Ninka Hoikuen (認可保育園) or Authorized Daycares

These daycares are authorized by the government after having fulfilled certain requirements to operate, such as having licensed workers, a certain amount of floor space, emergency exits, and a minimum number of daycare workers for children depending on the age group.

| Age Group | Number of Daycare Workers |

| 0-1 | 1 for every 3 children |

| 1-2 | 1 for every 6 children |

| 3 and up | 1 for every 20 children |

| 4 and up | 1 for every 30 children |

There are three main kinds of authorized daycares:

保育所 (hoikusho)

The most common type of daycare in Japan that focuses on child care for children ages 0 to 5 years old.

認定こども園 (nintei kodomoen)

A daycare that specializes in educating children ages 0 to 5. This is fairly new in Japan, having been introduced in 2006, and the most popular with parents as it integrates education that is taught in yochien (preschool). However, due to the limited number of nintei kodomoen, it is competitive to get into depending on where you live.

地域型保育 (chiikigata hoiku)

A smaller daycare that accepts a maximum of 20 children ages 0-2.

There are various kinds of chiikigata hoiku, such as ones run at someone’s home or by a company. My daughter attended a chiikigata hoiku managed by a kimono company.

These authorized daycares are operated either publicly by the city/ward or privately.

Authorized daycares that are operated and funded by the local government(公立保育園 or kouritsu hoikuen) are typically low in cost but there are very few of them. In fact, around 30% of all daycares in Japan are 公立.

As the government employs the daycare workers, they may be transferred to a different daycare each fiscal year.

Furthermore, all kouritsu within a city or ward are operated in a similar manner, such as the type of food they serve, events, etc. The buildings also tend to be old as well as the facilities, which was the case with the ones we saw when looking for daycares for our daughter.

Government-funded and privately-operated daycares are called 私立保育園 or shiritsu hoikuen. There are strict requirements in place for these daycares to receive and use funding. Unlike kouritsu, each shiritsu operates in its own way and is open for longer hours.

Muninka Hoikuen (無認可保育園)/ Ninkagai Hoikuen (認可外保育園) or Unauthorized Daycares

These daycares are not regulated by the local (municipal/prefectural) government and are operated by a private company. There are various reasons why a daycare may not be regulated by the government, such as size, hours, number of teachers, etc. However, one-third of teachers at muninka hoikuen should be licensed.

Parents tend to use these for various reasons, such as if their children did not get into ninka hoikuen or the daycare provides something that ninka hoikuen doesn’t, such as swimming lessons or English lessons.

Depending on the local government, parents may also get 補助金 (hojokin), which is a subsidy to help cover fees as muninka hoikuen costs usually are higher than authorized daycares and may include things such as an entrance fee. Some muninka also charge application fees. However, some muninka are both approved and subsidized by the national government and can end up being considerably cheaper than ninka.

Unlike application deadlines set by each city or ward for ninka hoikuen, muninka hoikuen have their own application schedule. For instance, we looked at an international daycare that was muninka, and their application deadline was at the end of October 2019 for April 2020 entry. However, a new muninka near our house started accepting applications in early March 2021 for April 2021 entry!

I’ve written in detail about my experience sending my daughter to both a ninka and muninka hoikuen, so please take the time to read this article if you want to know more.

Other Options

Ninshou Hoikusho (認証保育所)

This type of daycare is specific to Tokyo and certified, as well as funded, by the Tokyo government. There are two types of ninshou: A) which is close to a station, can take care of up to 120 children, and for children up to age five and B) a smaller facility which cares for as many as 29 children up to the age of two. Monthly costs are similar to muninka and you may be able to get hojokin, the monthly subsidy mentioned earlier, from the government to help offset these costs.

Ichiji Hoiku (一時保育) and Teikiriyou Hoiku (定期利用保育)

These are services that are provided by certain daycares (ninka or muninka) to help parents who need their child(ren) to be looked after temporarily due to part-time work, school, or other reasons.

You have to apply to reserve spot(s) for your child about a month in advance directly through the daycare as they only accept a limited number of children per day, which is decided in different ways depending on the daycare, such as taking into consideration whether both parents are working full-time, a lottery system, and so forth.

The way these services run as well as costs depend on where you live. For instance, some charge by the hour while others charge by the month, some have limits as to how many times a week you can use it, etc. Your city or ward office will have more detailed information, at the very least which daycares offer these services, so it’s best to ask them if you want to know more.

The Point System for Entering Daycare in Japan

Most cities in Japan use a point system to determine priority in terms of who gets a daycare spot in a ninka hoikuen. The higher your points, the more likely it is that your child will get accepted. The following are some situations that are likely to garner you higher points:

| No family members (ie. grandparents) residing nearby |

| Both parents are working full-time or a parent is on childcare leave and going to be returning to work |

| Low family income |

| More than one child |

| Single parent |

| Child is on a waiting list to get into daycare |

| Child is in muninka hoikuen |

You can also get points subtracted from your application. For instance, if your parents/in-laws are living with you and the city/ward can’t confirm that they can’t help with child care, the daycares you’re applying to are not in the ward or city you’re currently living in and you have no evidence showing you’ll be moving, you failed to pay daycare fees in the past, etc. Every ward and city is different so make sure you check with city hall or your ward office for more detailed information regarding the point system.

We were not told how many points we had (although some people in other wards or cities are informed so perhaps this depends on where you live) but to give you an idea of our situation when we applied:

- My husband and I both work full-time (more than 7 hours a day, 20 days a month) and in my case, I was intending on returning to my full-time job but was on childcare leave when we applied

- We have no family nearby who can help with our daughter

- We only have one child who was under the age of 1 at the time we applied and was not in any daycare

- We are not considered a low-income family

Steps to Apply to Daycare in Japan

The following are steps my husband and I took to get our daughter into daycare in Japan, but I can’t speak for every ward or city as they may have different procedures in place. All the information you need on how to apply to daycare, including application forms, can be found online. However, I think the first step that we took is a good one to take for all areas of Japan as the city or ward officials will be able to tell you exactly what to do and can answer any questions or concerns you may have.

1. Go to your ward office or city hall to attend a consultation session

Here you will find out about daycares in your area, the point system, etc. If you’re not sure which section or department to go to, head to the general reception (相談窓口) or the consultation counter for foreigners (外国人のための相談窓口) and ask them which department handles information on hoikuen.

It’s never too early to go in for a consultation — you can even go when you’re pregnant or if you’re thinking about moving to that particular city or ward and want to know about daycare options. Try to think of questions in advance as it can be hard to think on the spot at times (I always walk out of these things thinking, “Ahh, I should have asked A, B, and C!”) and the city/ward officials will be happy to answer.

The city/ward officials will also probably tell you the application schedule for ninka hoikuen, which is VERY important, so make sure to ask in case they don’t mention this or give you any printed material. You should also receive the application form for ninka hoikuen, but you can also find this form online and print it (Google something along the lines of 保育所申請書 and the city or ward you live in).

2. Visit daycares

This is not mandatory but I think it’s a good idea to visit the place where your child will potentially be spending most of their day and meet the people who are going to be taking care of them.

My husband and I began visiting daycares in October 2019 as the deadline in the area we live in to get into daycare starting in April 2020 was in December 2019.

First, we needed to call the daycares in advance to make an appointment to visit and the appointments were usually in the morning or early afternoon. They only accept a few parents at a time and on certain days so for some daycares we had to wait a month just to see the place! In total, we visited six daycares, five ninka and one muninka. I went with a mom friend to one ninka but preferred going with my husband to the others as I could get his opinion. (Note that given the current circumstances surrounding COVID-19, daycare visits may be temporarily suspended.)

We decided to aim to get our daughter into daycare starting in April as the beginning of the fiscal and school year in Japan gives you the best chance to get in. You can of course apply to get your child in at different times of the year as well — however, if you live in an area where daycares are competitive, it is likely your child will be waitlisted.

It’s also never too early to start looking at daycares, especially as children who are under the age of one have the best chance of getting in. There was one woman at a daycare 見学 (けんがく or visit/tour) we attended who was still pregnant!

If you’re wondering what to say when calling up a daycare to make an appointment, try this:

“見学の予約をしたいのですが、担当者の方お願いします。”

“Kengaku no yoyaku o shitainodesuga, tantoshanokata onegaishimasu.”

“I’d like to make an appointment to see the daycare.”

When it’s time to go, wear comfortable clothes as you’ll likely be sitting on the floor at some point, and try to wear socks as you’ll be asked to take off your shoes before you enter.

Try to also take your baby with you to see how the staff interacts with them and if the baby likes the surroundings. My daughter was only around three to four months old when we started visiting daycares but she enjoyed participating in storytime and playing with the older babies.

(I will admit, though, that I drew some unwanted attention from kids due to being foreign and got comments like, 英語の人がいる and the timeless classic, 外人!I did not choose those daycares for my daughter in the end as the daycare workers ignored it and I felt like those same kids might bother my daughter.)

Make sure to also bring a notebook and pen with you and feel free to ask the staff any questions you have about the daycare. There will usually be a question and answer period at the end of the tour. The daycare should also provide you with a pamphlet about their facility.

You might be wondering what questions to ask. Try to visit the daycare’s website in advance. If there’s any information that’s lacking, such as hours of operation, things you have to prepare and bring for your child on a daily/weekly/monthly basis, what happens if your child is sick, meals, events you have to attend, how often they sanitize toys, qualifications/licensing of staff, etc., then the 見学 is your chance to clarify things.

Below are some questions that may be a helpful start if you’re not sure where to begin:

In Japanese

- 保育料、追加費用はありますか?

- 預けに行く時間と向かいに行く時間は決まってますか? 親が遅れる場合(通常の向かいに行く時間の後)、

追加料金はかかりますか? - 一クラスあたりの子供の数は?

- 別のクラスと遊んでいますか?

- 毎日のスケジュールは? 昼寝は何回ありますか?

- 食事はどんな物を取ってますか?

- 両親は預けに行くと向かいに行くで何をしなければなりませんか?

- 保育士はおむつを捨てますか?

- 保育士はどのように親とコミュニケーションを取りますか?

- 建物はどのように作られていますか?

- 自然災害が発生した場合、

子供たちはどのように守ってくれますか? - タッフはマスクをきちんと着用していますか? (鼻の上)

- 部屋はどのくらいの頻度で掃除されますか?

- 子供たちは外のどこで遊びますか?

- 保育士は応急処置の訓練を受けていますか?

- What are the daycare fees? Are there any additional costs?

- What are the hours? If a parent is late (after normal pick-up time), is there an additional cost?

- How many children are there per class?

- Do different classes interact with one another?

- What is the daily schedule? How many naps are there in a day?

- What is the food menu?

- What do parents have to do at drop-off and pick-up?

- Does the daycare throw away diapers?

- How do the daycare teachers communicate with parents?

- How is the building made?

- In the event of a natural disaster, how are the children protected?

- Do the staff wear masks properly? (Over the nose)

- How often is the daycare cleaned?

- Where do the children play outside?

- Are the daycare teachers trained in first aid?

(Thanks to fellow mom Tari for contributing to these questions!)

3. Apply

Muninka applications should be given directly to the daycare to which you’re applying. If you’re applying to ninka, your application form should be given to the ward office or city hall.

The deadline to hand in the application form for our area was the end of December so we went and handed in everything right before Christmas. We were also asked to bring our daughter when we handed in the form and I had to also fill out some additional paperwork but it was all over pretty quickly.

You can apply to as many ninka as you want as it’s all on one form but list your daycare choices in order of preference. We applied to only two daycares, both ninka, because those were the only ones we liked and felt comfortable leaving our daughter. If you don’t get into your first choice, you can try to re-apply while your child is attending the daycare they got into.

However, note that if you don’t get into your first choice and decide not to enroll your child into the daycare to which they were accepted, you will be penalized and it will be harder for you to get another daycare spot when you apply again. This is why it is very important not to write down the name of any daycare you do not want your child to attend on the application form.

My husband and I were also required to submit forms to confirm our employment and work hours. HR at our companies filled out these forms and mailed them back to us, which we then submitted with our application. Make sure you give your company ample time to complete these forms as the last thing you want is for it to be delayed.

Keep in mind that these documents are usually in Japanese only and very bureaucratic, so do not hesitate to ask for help from a friend or coworker if you need it, especially as one mistake can delay your application. Also, make sure to give yourself plenty of time to fill out the application and do not wait until the last minute.

4. Wait

We were told that we would receive the results at the end of February 2020. Sure enough, the last week of that month a letter came in the mail and we got a big surprise — our daughter got into our first choice! I was a mix of relieved, disappointed, and shocked. It was a very confusing time because I wasn’t completely ready to go back to work and lose time with her. (However, she only went to daycare for three days in April before it was closed due to a certain virus. She then stayed home until June, so I did end up getting additional time with her, which I was grateful for.)

My friend’s daughter, who is around the same age as mine, also got into a daycare in the same area, but given that the daycare facility is brand new and thus had no waiting list, and is also very far from the station, perhaps it isn’t that much of a surprise.

If your child did not get into daycare, they will be waitlisted and if a spot opens up at one of the daycares you listed on your application form, you will be contacted by city hall or your ward office.

As I’ve mentioned before, the area we live in is famous for its long daycare waitlists and we were confused about why our daughter got in since our points didn’t seem that high; however, the daycare my daughter is going to is a chiikigata hoikuen, which may be why we got in as not many parents want to go through the trouble of finding another daycare before their child turns three. We aren’t anticipating living in this area when our daughter is three so we had no problem applying.

2022 Update!

As some of you may know, my family moved to Osaka near the end of 2021. We had only one week at the beginning of December to look at daycares and apply, and unfortunately, since the area we live in now is quite small, there wasn’t much to choose from and many kids on waiting lists.

We applied to only one daycare and as I’m not working full-time, we weren’t surprised when at the end of January we found out that our daughter didn’t get into the daycare. In fact, she wouldn’t have gotten into any since there was zero space for kids her age (2歳児 / two-year-olds) and up.

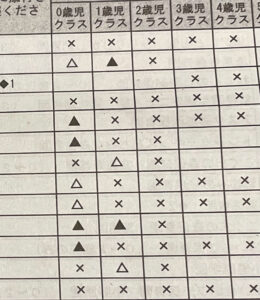

Children who get into daycare at an early age (so into the 0歳児 class) tend to stay at the daycare, and although more spots open up for 1歳児 (one-year-olds), it’s very competitive and those children tend to stay as well, leaving little to no spots if you want to try to get your child into daycare when they’re older.

As you can see in the image below, it is indeed much easier to secure a spot if you try to put your child in daycare as soon as possible.

x marks… no spots!

My daughter eventually ended up going to pre-yochien before she was accepted into yochien a few months earlier than the usual age of acceptance.

Note that this does not mean your child cannot get into daycare if you’re not working (or not full-time)! It depends on a number of factors, such as the popularity of the daycare, if the area you live in has lots of families with young children, etc. And remember, if you tried for a ninka daycare and couldn’t get it, try looking for muninka daycares!

Daycare Costs in Japan

As I briefly mentioned earlier when going over the different types of daycares in Japan, monthly costs for ninka hoikuen are calculated according to your family income, so the more you make, the more you have to pay for daycare. This payment scale varies according to your city/ward, so daycare fees in some wards in Tokyo are much cheaper than others.

For instance, Shibuya-ku and Chuo-ku have the lowest daycare fees in Tokyo while Sumida-ku and Koto-ku have the highest. So depending on your family income and where you live in Tokyo, you can pay as little as 7490 yen per month for daycare or as much as 77,700 yen. For a detailed list of the cost of daycares in various wards in Tokyo, check out this site (in Japanese only).

The cost of daycare also varies depending on the age of your child — the younger your child, the higher the cost but it will go down as they get older.

Muninka can be more expensive or cheaper than ninka depending on the type. We sent our daughter to a new muninka before she turned two and ended up paying much less than what we paid for ninka.

Note that apart from meals, hoikuen becomes free for children ages three and up! However, this doesn’t mean that hoikuen will be free from the moment your child turns three. This depends on the school year, meaning that your child must be three by the start of the Japanese school/fiscal year (April) before it’s free. For instance, if your child turns three in let’s say May, you’ll have to pay for hoikuen until April of the next school year.

What to Consider When Choosing a Daycare in Japan

1. Location

Ideally, the closer to your home the better. We knew we wanted to move to a bigger place that was closer to the station, so we chose a daycare near the station as our first option as no matter where we moved we knew we would have to go to the station to commute, and I’m so glad we made that decision.

We then lucked out when a muninka opened a two-minute walk from our house!

My workplace also has a daycare facility for children of employees that’s a two-minute walk from my office; however, I did not feel comfortable taking my daughter on the train and decided against that option.

2. Costs

Costs vary depending on the daycare, such as initial costs and possible additional costs if your child is at daycare after normal operating hours. For instance, at the ninka my daughter attended, we had to pay about ¥6000 in initial fees for our daughter’s hat, helmet, bags, etc. However, at the muninka she attended the following year, the monthly fee was less than the ninka and we didn’t have to pay any initial fees. They also provided diapers and wipes for free!

Note that this isn’t the case for all muninka, so we were very lucky.

3. Age Group

Some daycares only accept children up until the age of 3 while others accept children up until they start elementary school. This is something to keep in mind if you don’t want to go through the hassle of finding another hoikuen or yochien (preschool) before your child turns three. However, if you don’t care about this or you’re planning on sending your child to yochien, then these types of daycares might be a good option as they are not as popular, and thus your child has a better chance of getting in.

We were intending to move within two years, which is why we didn’t care that the daycare our daughter got into is only up until the age of three.

4. Space

If you’re searching for a daycare in Tokyo or another big city in Japan, space can be an issue. A lot of the daycares we looked at were very small with little to no natural light, which I really disliked, and had no space for the children to play outside. Daycares do, however, tend to take kids out on walks if the weather is nice so this may not be such a dealbreaker for some people.

The ninka my daughter attended was small with no space to play outside. However, the muninka was bigger with a yard as well.

Soon after we moved to Osaka, we looked at a few daycares and found that the ones closer to the station were very small with no outdoor space. Daycares that were quite far from the station were massive, had a huge yard, and were overall quite nicer than the ones we saw in Tokyo.

5. Staff

This is really important because these are the people who are going to be taking care of your child and you are going to be interacting with them almost every day. The last place you want to leave your child is somewhere the staff make you feel uncomfortable. What I liked about both daycares my daughter attended is that the staff treated me pretty normally. We could also see that the children clearly liked the staff and my daughter did, too!

She still asks about two teachers and clearly misses them, which shows what wonderful people they are and how much they made a positive impression on my daughter.

6. Cleanliness

This was also a big one for me because I am a neat freak. I know cleanliness and children don’t really mix and my husband is constantly telling me that my expectations are too too high (he made me write the extra “too”, by the way) but I wanted my daughter to attend a relatively new daycare with clean facilities and no clutter. This is exactly what I got with both daycares she attended.

In my next posts in this series on daycare in Japan, I’ll share information about how I prepared for daycare, as well as my daughter’s first two weeks of 慣れ保育 (narehoiku), and the 連絡帳 (renrakucho), an essential communication tool between you and your child’s daycare.